To admit that I bought Dmitry Samarov’s All Hack in part because I was overwhelmed by his generosity is not a stretch. He reviewed my novel for Maudlin House earlier this spring and said very kind things about it, and then had me on his podcast: a two hour conversation as enjoyable as I’ve had with another writer in eons. So if, in reading the following post, well, you’re welcome to be suspicious that I’m returning a favor. But I’m emphatically not. I’m a poor liar and have enough trouble saying nice things about writing I dislike to the writer when they’re sitting across the table from me. Just can’t do it. To do so in a published piece would be even more difficult if not impossible. Ever since I had the ignominious privilege of dressing down a book by a friendly acquaintance in that writer’s hometown alt-weekly back in 2016, a task that I did not particularly enjoy, I’ve stuck to the policy not to review books by friends or even close acquaintances unless they don’t know I’m going to write about it until the review appears—thus saving me from both impulse to cushion the blow and the gnawing awareness that I will not ultimately be able to play nice.

As a reviewer, playing nice isn’t something I’m good at anyhow. One of the reasons I’ve written so few reviews over the past couple years goes back to 2021, when I had not one, not two, but three different reviews killed simply because they were—at least in the minds of those publications’ editors—those being the Harvard Review, Public Books, and Literary Review—simply too damn mean. I posted one of those here.

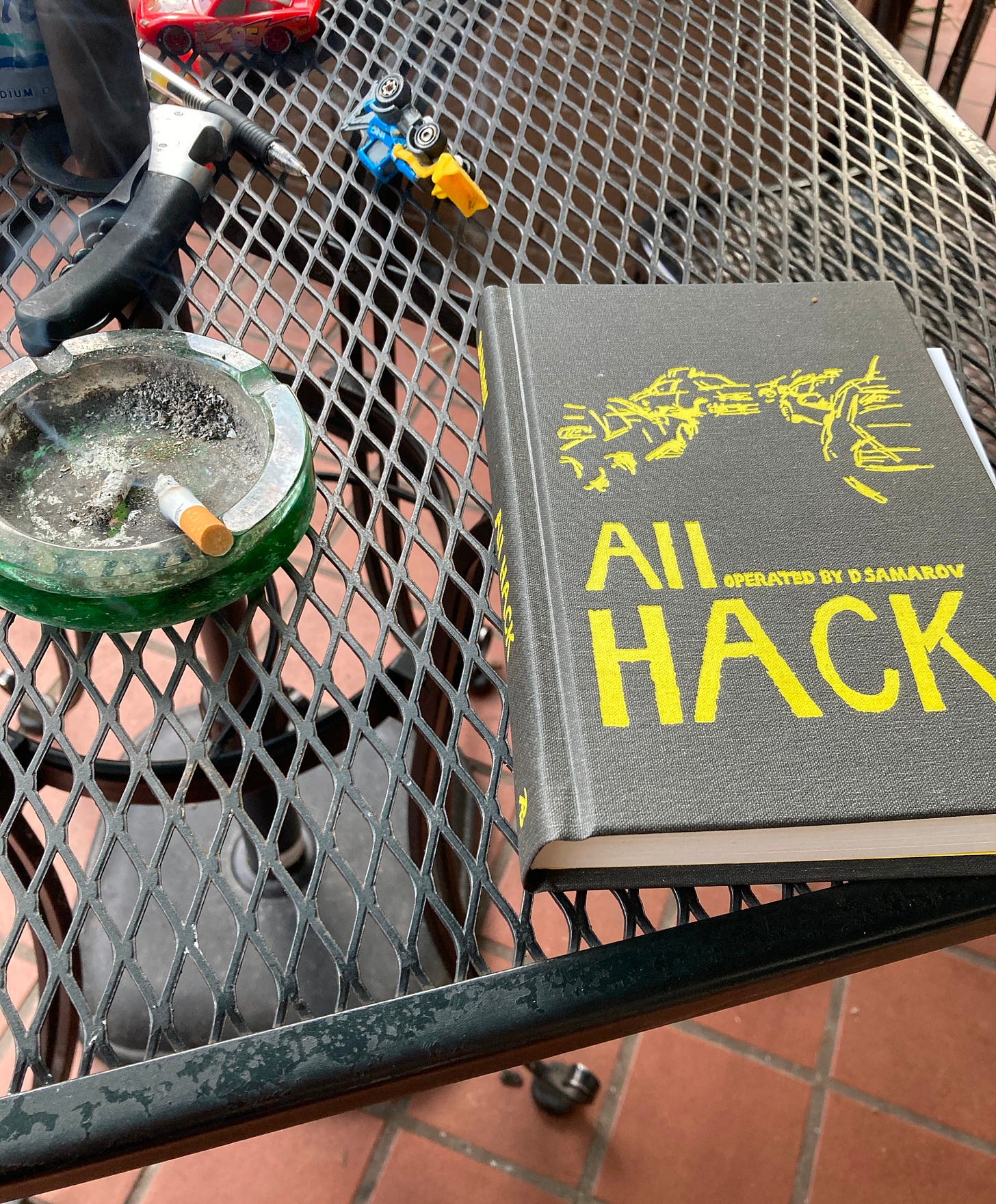

All that to say: I opened Dmitry Samarov’s All Hack one day last week around one o’clock in the afternoon and, aside from breaks to fetch my child from school and then to make and eat dinner, I didn’t stop reading until around eleven that night, when I reached the end. The book, a collection of all of Samarov’s writings about his years as a cab driver in Boston from 1993-1997 and in Chicago from 2003-20012, is a goddamn marvel, featuring one short piece after the other interspersed with Samarov’s paintings and sketches. Each piece is narrated in the first person by someone who more or less seems to be Dmitry himself. Taken together they form a collage of a life or major part of a life spent working in America, doing the kind of job that many Americans increasingly find themselves stuck in: thankless, low-paid, and exhausting, and yet, for Samarov, a vein of material so rich that he couldn’t avoid taking up that other low-paid or usually no-paid job: that of a writer. I’m glad he did.

Samarov has described himself as a painter-first, writer-second, and the paintings and sketches interspersed throughout the book provide a sense of mood and tone that gives his writing a kind of grain or texture that both goes beyond and illuminates his written prose, which proceeds across the page with an unflashy directness that has the quality of someone sitting next to you at a bar. I don’t mean to say the writing is conversational, exactly, in the same way as one might describe the writing of someone like Scott McClanahan, a writer who really sounds like he’s talking to you about his life in West Virginia, but rather to say that Samarov’s writing proceeds with a kind of distinctly urban candor: the narrator of these pieces doesn’t waste anymore language on the page than he does in person to the drunks he frequently finds himself carting from one bar to another. “I pick him up at the Gas For Less station on Lincoln,” writes Samarov. “He is overweight and a little disheveled but otherwise doesn’t seem unusual. He gets in and says, ‘You know where I’m going.’ I don’t and tell him so. We debate it for a good five minutes: he can’t believe it; he is convinced I know.” Eventually the guy tells him where to take him. They head to the Lathrop Homes projects. The guy gets out and is directed by some “young entrepreneurs” to a window “at which he proceeds to scream at the top of his lungs, ‘GIVE ME DRUGS!!!!!’” The so-called entrepreneurs give Samarov “a look that says, What have you unleashed on us?! I decide then that there has been enough entertainment for the evening and tear out of there without looking back.”

One of the book’s through-lines is the astonishment its author often encounters at being a so-called white cabbie, and the ways he allows the speakers of this subtle—or just as often overt—racism to incriminate themselves. Being Jewish and born in Moscow—he immigrated with his parents to the US at around the age of ten—English isn’t his first language. A persistent thread throughout is a feeling of displacement, of not having found a place in this country; what ultimately interests me most about this feeling is that the book feels distinctly American precisely in the anecdotal quality of its narration. Like the aforementioned McClanahan, and like the great Charles Portis, Dmitry Samarov raises the anecdote to a high art. Part of what’s interesting about this is that the American anecdote—the art of telling the story either on bar stool or front porch—is almost exclusively the department of rural writers writing about predominantly rural people. Samarov, though, is all city. He has a simple story to tell and he tells it and then he tells another. And then another. Most of these snippets—moments?—simply begin somewhere, on some foggy Chicago street corner, and they don’t always have a distinct beginning-middle-and-end, and many of them are not particularly remarkable taken on their own, and yet, taken together, they acquire a kind of palatable emotional force that only occurs in the work of a writer who has lived his work, transforming it into an incredibly moving collage of a life spent behind the wheel of that most American of objects, the automobile. It is not a machine the writer loves but one that both enables him to make a living and one that, as I mentioned above and in his own words, fundamentally changes him into someone who can’t help writing. And yet part of what interests me most about this work is this: despite obviously being autobiographical in the sense of not being made-up—Samarov confesses this somewhere or other in the book and said much the same when we spoke—the fact that the writer writing all this and the character doing all this driving remains for most of the book in the background. We almost never see him in his off hours and learn almost nothing about his personal life. He hates Wrigleyville and loves the White Sox and seems to have a prodigious talent for being awake at strange hours. That’s about it. His is a life spent at the wheel, taking his customers from street to street and his readers from page to page.

Perhaps part of what appeals to me so much about this book, I think, comes from my own time spent behind the wheel—admittedly far, far less than Samarov’s. I’ve had two separate stints as a pizza delivery driver, both before the age of GPS, in Stillwater, OK and in Seattle, plus a short stint as an Uber driver, and in my current job as a college instructor I regularly spend more than 2.5 hours a day driving back and forth between Nashville, where I live, and Clarksville, where I teach. There’s a peculiar loneliness that develops when you spend a lot of time in the car alone. A gnawing feeling, too, nags at you that you could be somewhere, doing something you actually want to do, like making art or hanging with family or friends, or simply watching TV, but instead you’re nowhere in particular, driving your increasingly run-down car from one place to another that you either don’t know or about which you have no particular feelings, largely at the mercy of the rest of the public out there on that same road, burning all that gas and time all because you’re trying to scratch out some coin.

In most autobiographical writing a portrait emerges. The difference here is that in All Hack we glimpse not the image of the writer but that of a great city, Chicago, with all that town’s joy and bluster and despair and drunkenness and petty meanness: its blizzards and breezes, its trips to the fast-food joint, police station, home front door and, ultimately, with a kind of bigheartedness rarely seen in depictions of this increasingly miserable country’s working life, its human beings.

Wow. Thanks so much for this! Might be the most generous read I've ever gotten.

great review man, loved it.